|

|

|

The GI Joe

Coastwatcher

Of New Britain

Here's a GI JOE project that was

intended to be historical in nature. While my kids and I learned about

the heroic WWII Coastwatchers, we built our own - a GI JOE

coastwatcher! This webpage contains historical Coastwatcher info

followed by details of making our own "Joe" Coastwatcher. Note that we

did this project before the TC Aussie was announced - too bad we wasted

a vintage Japanese uniform to make it!

The REAL

Coastwatchers

After the attack on Pearl

Harbor on December 7th 1941, civilian coastwatchers provided

valuable intelligence regarding Japanese aircraft and ship movement in

the area around New Britain, New Ireland, and other nearby islands.

Trading ship skippers, missionaries, planters, and a host of other

Allied-sympathetic civilians provided Australian naval Intelligence of

activity in their areas. This effort kept the Australians advised of

any suspicious, unusual, or dangerous events unfolding nearby.

After the attack on Pearl

Harbor on December 7th 1941, civilian coastwatchers provided

valuable intelligence regarding Japanese aircraft and ship movement in

the area around New Britain, New Ireland, and other nearby islands.

Trading ship skippers, missionaries, planters, and a host of other

Allied-sympathetic civilians provided Australian naval Intelligence of

activity in their areas. This effort kept the Australians advised of

any suspicious, unusual, or dangerous events unfolding nearby.

On January 4, 1942, the Japanese began bombing Rabaul and its airfield on the island of New Britain. On January 20th, more than 100 bombers with fighter escort arrived over Rabaul. The last message out of Rabaul was from Wing Commander John Lerew leading a flight of Commonwealth CA-3 Wirraway training aircraft into battle: "Nos Morituri te salutamus" ("We who are about to die salute you", was the Roman gladiator’s salute.) Two Wirraways and a lone Hudson bomber survived the attack and were withdrawn from Rabaul. The next morning, 5,000 Japanese troops, backed by 4 aircraft carriers, two battleships, carriers, and destroyers, arrived at Rabaul. Within 24 hours, all of the Allied Rabaul garrison defenders were dead, captured, or fled into the jungle.

Now the coastwatchers on New Britain were all behind enemy lines. Being a coastwatcher or aiding a coastwatcher was a dangerous business; when captured by the Japanese they were summarily beheaded.

After the Japanese landing on New Britain, the island was teeming with Japanese troops. One by one the Coastwatcher’s radios on New Britain, New Ireland, and the nearby islands fell silent.

Despite the intense pressure from the Japanese, some coastwatchers continued to operate. Cornelius Page and Jack Talmadge set up a spy network on New Britain. For five months they reported on the and the Japanese buildup at Rabaul, including ship and aircraft movement. They were ultimately captured, taken to Kavieng and beheaded.

New Britain was silent, without coastwatchers, until November of 1942. In anticipation of an American/Australian offensive on Lae, the Allies placed intelligence parties on New Britain to provide INTEL on Japanese movements pending the invasion. By now all coastwatchers had been given military ranks - in hopes that they would be accorded POW status if captured, instead of being summarily executed. As expected, this commissioning was in vain. Being a coastwatcher remained an "all or nothing" proposition. The offensive on Lae was delayed by the extended battle for Buna. The Coastwatchers on New Britain were captured and executed. Only a few of the coastwatchers who landed on New Britain managed to evade capture. They lacked the ability to blend in with the islanders, and could not expect cooperation from the local inhabitants of the islands; they were in constant danger of betrayal.

At the request of the U.S. Navy, coastwatchers were placed on New Britain’s south coast between Wide and Jacquinor Bays in an area called Cape Orford. This area wasa mountainous and lightly populated, so the coastwatchers might have a chance to survive there for a while. The coastwachers were transported by submarine in February of 1943. They set up camp in the jungle and built platforms in tall trees to facilitate their ability to observe and report sightings of Japanese air and sea traffic in the area. They befriended Golpak, the native chief of the area, who did not like the Japanese at all. A great ally, he ensured the silence of his people and helped set up a spy network across the island. This group operated for five months, reporting 70 enemy subs, over 100 aircraft, and a large number of supply ships and barges.

Later in 1943, another 16 Australian and 27 native coastwatchers were landed at Cape Orford by the US sub Grouper. After landing, they split into five groups and headed off over the mountains or along the coast to their areas of operation. One of these parties, led by Captain John Murphy, was betrayed by some natives, and they were captured by the Japanese. Murphy’s group were all killed, while Murphy himself was wounded but captured alive. He was taken to Rabaul, tortured, and subjected to medical experiments. (Surprisingly, Murphy survived the war!) The discovery of Murphy’s group alerted the Japanese to the presence of coastwatchers again on New Britain. This caused the Japanese to dispatch search parties once again, in an effort to rid the island of Allied coastwatchers. Most of the coastwatcher groups had to remain constantly on the move and abandon any thought of fixed observation posts. Their survival depended upon mobility.

One group (the Kirkwall-Smith group) had reconnoitered the Arawe and Cape Gloucester areas for 12 days prior to an Allied landing. In December, the U.S. Marines landed at Arawe and Cape Gloucester, relying upon the Coastwatcher’s intelligence. Coastwatcher Les Ashton was with the Marines on the Cape. Coastwatchers radioed warnings of Japanese air and troop movements to Les Ashton, who would immediately inform the Marines of the latest developments. Thus the U.S. Marines could take rapid defensive action.

After the Arawe and Cape Gloucester invasions, General MacArthur’s leapfrogging advance across the Pacific isolated the Japanese troops on New Britain. The Coastwatchers continued to operate, pinpointing targets for Allied air attack on the island, although they were still under constant pressure from native-led Japanese patrols. In view of their tenuous position, and the dim prospect of any renewed strategic focus on the island, the coastwatchers asked the director of the coastwatcher service for permission to fight the Japanese patrols – and were pleased when their request was granted. Native soldiers along with Australian officers and NCOs were landed on New Britain to assist in this new aggressive role. Shotguns and rifles were dropped by parachute to arm local recruits. Due to their extensive experience in the jungle playing "cat and mouse" with Japanese patrols in an effort to avoid detection, the coastwatchers had learned the skills of guerilla fighting out of necessity.

One group of coastwatchers, Wright, Searle, and Simogun, moved into the interior region and came across the Nakanai tribe, who had little contact with the Japanese (but were spoiling for a fight with the invaders). The coastwatchers led the Nakanai warriors against any Japanese patrols that came within striking distance, though the Nakani warriors were often armed with only bows and arrows. Two of the coastwatcher guerilla fighters, Simogun and Makelli, distinguished themselves in what the coastwatchers called "shoot and scoot" tactics. In one encounter, Simogun and some natives encountered 20 Japanese soldiers in the village of Umo. Simogun stepped into the open and leveled his Owen submachine gun. After a few shots, the gun jammed. In full view of the Japanese troops, he was an easy target. While the Japanese fired at him with abandon, he calmly changed magazines and resumed firing. He killed 5 of them with one burst, and the remainder of the patrol fled the village as fast as they could run. In another encounter by this group, Simogun’s corporal, Pasilanga, stepped out onto a path to confront a Japanese patrol. He fired a shot from his rifle at close range. To his surprise, three scouts fell. (The first two were killed and the third mortally wounded.) The rest of the honorable warriors in the patrol immediately turned and fled. In two months, the total number of Japanese killed had reached 286, while the coastwatchers suffered only 2 casualties. For the coastwatchers, who had been captured and executed with impunity by the Japanese, this was a time of reckoning. After the conflict, Allied patrols found hundreds of Japanese corpses in the swamps; they had been driven into the swamps by coastwatcher attacks, where they ultimately starved to death.

Captain B. Fairfax-Ross had an extensive history as a prewar planner and had served with the military in the middle east as well as on the New Guinea mainland. He came late to New Britain to organize the guerilla groups to clear the Japanese from New Britain. Thanks to the aggressive Coastwatchers, when the Australian troops arrived and advanced along the north and south coasts to seal off the Gazelle Peninsula, they encountered little organized opposition.

Throughout the war, coastwatchers routinely praised their native police, soldiers, and guerillas who worked with them. Their efforts undoubtedly helped turn the tide of war in the Pacific, by providing indispensable intelligence and constant pressure on the Japanese forces occupying New Britain, New Ireland, and the surrounding islands.

Source: This material has been edited

from the Undercover column of World War II Magazine, May 1998,

page 8+, in an article entitled "Coastwatchers on New Britain

provided intelligence and helped to keep the Japanese bottled up at

Rabaul", Cowles History Group, Inc.

The

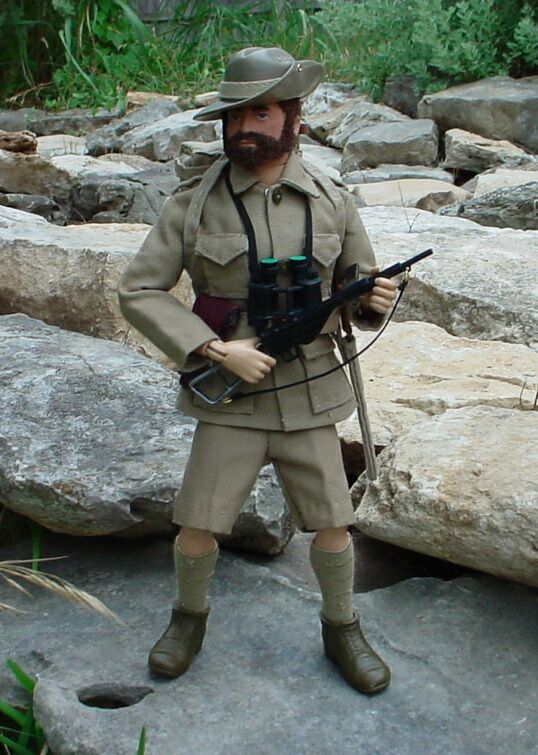

GI JOE Coastwatcher

The GI Joe Coastwatcher uniform came about more by accident than by design. I stumbled across several vintage Japanese uniforms at a flea market in the mid-80s, and bought them all. I didn’t really have much interest in Japanese infantry at the time, so I resold most of the uniforms at giveaway prices (and ended up giving several of them away). I was stuck with two that I couldn’t even give away. I’d always liked the look of the Australian jacket and the Desert Patrol Jeep driver version of the jacket, but could never afford one at a convention or online. After becoming interested in the Coastwatchers (primarily from the article cited above) I decided to use one of these unloved vintage Japanese uniforms to make a custom GI Joe Coastwatcher. I ran across a KFG AT Land Adventurer in the Sandbox for sale and my project began! I replaced the rotten KFG with Cots Actin Hands and began working on the Japanese uniform…

The trousers were easy: I just cut off the Japanese trousers above the leggings and hemmed them with khaki thread. I decided to use the leggings as knee socks for the figure, so I turned them upside down, putting the unhemmed "top" of the legging down into the boots out of sight.

For the jacket, I used a second pair of vintage Japanese trousers as

a donor for material. I cut up the trousers to make pockets and flaps.

The figure already had upper pocket flaps, so all I had to do was make

a pocket to match. I added the lower cargo pockets and flaps out of the

same material. I carefully removed all insignia with a pair of

tweezers. The glue was so dried out that no other preparation to remove

them was necessary. I still had a bit of cloth left over from the donor

uniform, so I used the cloth to make epaulets and side flaps for the

jacket. Recall the flap on the Desert Patrol Jeep jacket? It was

designed to clip on a .45 holster or canteen. These can be used in a

similar manner, making the jacket even more versatile!

No self-respecting Coastwatcher would be without a radio. I had a spare

French Resistance Fighter morse radio kicking around but didn’t like

the layout. So I modified the interior (shown at left) to suit my

fancy. I tried to re-use the original stickers to keep the "vintage"

look about it.

To carry this radio, I made a backpack specifically for this

purpose, along with space to accommodate the vintage 2-piece British

entrenching tool.

I picked up an AT "Aussie" hat at a San Antonio Joe Club meeting,

along with a khaki 1st aid pouch for Joe’s belt. The junk

box provided a pair of Coast Guard CC binocs that looked period. I

added some repro Cots low brown boots for tromping through the jungle,

and a vintage Sten gun to keep the Japanese pursuers at bay. The

holster and canteen cover were both made from thin leather and hand

sewn. I decided to make the holster a "cavalry draw" style holster – a

left handed holster worn on the right side - just for variety. Somehow

it looked more "British" or "Aussie" that way. The machete was made

from 3 pieces of sheet plastic, one in the profile of the blade and

tang, and two in the profile of the handle. With a little Tamiya

acrylic paint, it came out very well. The machete sheath was hand-sewn

as well. When making a sheath (or holster) from twill cloth, it

pays to make a solution of 50% water 50% Elmer's glue and soak the

sheath/holster in the solution until it's thoroughly saturated.

When it dries, it'll be stiff and feel/look like military canvas.

I think I may have left the machete in the sheath as it dried, to

better hold the shape of the blade as it hardened.

Just by swapping out the Sten for a Palitoy hunting rifle and adding AT

brown trousers, Joe transforms into a general-purpose AT Explorer,

ready for anything from mummies to white tigers.

This collection of items, along with those specially made for the

project, ultimately became the GI Joe Coastwatcher, ready to

take on any challenge at some remote Pacific island, or in the

desolate, remote reaches of our own back yard!

Click the logo to go to the AT Headquarters home page ![]()